Stuttering. The flow of human communication a seamless stream of thoughts translated into sound is something most of us take for granted.

Yet, for an estimated 5% of the global population, this flow is often interrupted by an intriguing and sometimes debilitating speech disorder known as stuttering (or stammering).

While it frequently emerges in early childhood, typically between the ages of 2 and 7, and resolves spontaneously for the majority, a significant number of people carry this challenge into adulthood.

The quest to understand the root causes of stammering and to find definitive, universally effective treatments has engaged scientists, speech-language pathologists, and neuroscientists for centuries.

Though a single, precise answer remains elusive, research continues to illuminate the complex interplay of factors primarily neurological and genetic that give rise to this unique phenomenon.

Stuttering, Historical Look.

Stammering is far from a modern affliction; historical records confirm that people have grappled with speech disfluency since ancient times. This challenge has touched individuals from all walks of life, including those of great renown.

Figures of history like the Greek orator Demosthenes, the scientist Isaac Newton, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, and even the “King of Rock and Roll” Elvis Presley are all noted to have struggled with stuttering, particularly in their youth.

The sheer persistence of this phenomenon across cultures and eras suggests a deep-seated biological or psychological mechanism.

For instance, mentions of stammering have been found in Aztec hieroglyphs, where the condition was erroneously linked to prolonged breastfeeding. Their ‘treatment’ involved weaning the child and introducing solid food a prime example of early, unfounded, and non-scientific attempts to cure the condition.

Such historical accounts underscore the long-standing human endeavor to explain and address this speech difficulty.

The Intricate Neural Basis of Stammering.

Modern research has largely moved away from purely psychological or environmental explanations for the onset of stuttering, focusing instead on the intricate workings of the brain.

Experts now largely agree that developmental stuttering has a neurobiological basis, affecting the brain systems responsible for planning and executing speech.

The Brain’s Speech Center Disruption.

Studies using advanced brain imaging have revealed significant differences in the brain anatomy and function of people who stutter (PWS). Key areas involved in this disruption include:

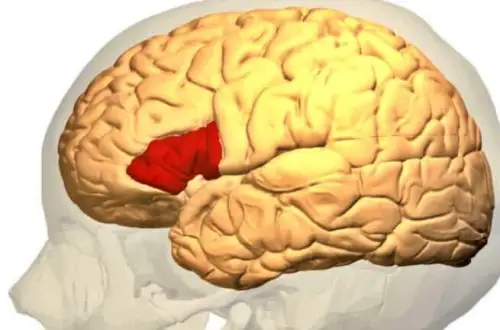

Broca’s Area (Left Inferior Frontal Gyrus – IFG).

This region is critical for speech production and language processing. Research has indicated reduced blood flow or under-activity in this left-hemisphere speech center in PWS, suggesting an impairment in the efficient execution of speech movements.

The Right Hemisphere.

A Case of Over-Inhibition: Interestingly, many PWS show hyperactivity in areas of the right cerebral hemisphere the side typically less dominant for speech. Specifically, an overactive right IFG and tightened connections within the Frontal Aslant Tract (FAT) are often observed.

In a neurotypical brain, the right IFG may act to inhibit movement; its overactivity in PWS is hypothesized to interfere with the smooth, timely initiation and execution of speech that is primarily handled by the left hemisphere, causing a kind of “stop signal” that disrupts the flow.

Altered Neural Connectivity.

Stuttering is often associated with differences in the white matter tracts (the “wiring”) connecting the speech and language areas. For example, some PWS show weaker connections between areas responsible for hearing (auditory feedback) and those generating speech movements, suggesting a failure to properly integrate information crucial for fluent speech.

The Role of Astrocytes and Genetics.

Beyond broad functional differences, research is beginning to zero in on specific cellular and genetic mechanisms:

• Astrocytes: These star-shaped glial cells, which perform numerous support functions for neurons, have been implicated in the development of stuttering in children. While their precise role is still being investigated, their involvement suggests that the issue is not simply a matter of how neurons are communicating, but also the fundamental support structure and cellular environment within the brain’s speech pathways.

• Genetic Predisposition: The strong tendency for stuttering to run in families provides powerful evidence for a genetic component. Although multiple genes are likely involved, researchers have identified specific genetic mutations that may increase a child’s susceptibility to the disorder. This is considered one of the most consistently reported statistics: approximately two out of three people who stutter have a family history of the condition.

Classifying Disfluency.

Forms of Stuttering.

While the common perception of stuttering involves an obvious, audible break in the flow of speech, the disorder manifests in various ways, categorized both by the nature of the interruption and its presumed origin.

By Manifestation (Core Behaviors).

• Clonic Stuttering: Characterized by repetitions of sounds, syllables, or single-syllable words (e.g., “b-b-ball” or “I-I-I want”). This is the classic, often rapid, and involuntary repetition of speech elements.

• Tonic Stuttering: Characterized by an unnatural prolongation of sounds or an articulatory block (e.g., “Mmmmommy” or an inability to produce sound at all, often accompanied by visible tension). This involves an inappropriate tensing of the speech musculature.

By Origin (Etiological Types).

• Developmental Stuttering: This is the most common form, typically beginning in early childhood (2-5 years) as the child’s speech and language skills are rapidly expanding. It accounts for the vast majority of cases and is strongly linked to the aforementioned genetic and neurobiological factors.

• Acquired (Neurogenic or Psychogenic) Stuttering: This is much rarer and occurs in older children or adults.

* Neurogenic Stuttering results from brain damage, such as a stroke, traumatic brain injury, or certain degenerative neurological conditions. This type can affect all speaking situations, including reading or repeating, and often doesn’t show the secondary struggle behaviors typical of developmental stuttering.

* Psychogenic Stuttering is associated with an acute emotional trauma or underlying mental health condition. This is very uncommon and requires a distinct therapeutic approach.

The Impact of Secondary Behaviors.

Nearly all PWS eventually develop secondary behaviors in response to the primary disfluency. These are learned physical movements or verbal tricks used in an attempt to “push through” a block or repetition. Examples include:

• Facial Grimaces or Tics: Eye blinking, jaw jerking, or lip pressing.

• Unnecessary Movements: Head jerking, foot tapping, or fist clenching.

• Avoidance Behaviors: Substituting difficult words, avoiding certain speaking situations, or inserting filler words (“um,” “like”) to temporarily delay speaking.

Environmental and Psychological Factors.

While the primary cause of developmental stammering is neurological, environmental stressors can significantly contribute to its onset, severity, and persistence, particularly in children who are already genetically susceptible. These are not causes, but risk factors:

• Family Dynamics: Conflictual home environments, overly critical parents, or high-pressure communication demands can exacerbate the problem.

• Imitation: Although not a direct cause, exposure to other people who stutter in a child’s immediate environment may sometimes influence the child’s own emerging speech patterns.

• Multilingualism: The early, simultaneous learning of two or more languages can be a risk factor in some cases, likely due to the increased cognitive load on the developing language system.

• Insufficient Communication: A lack of attentive, relaxed, and unhurried conversation with caregivers can also be a stressor.

Furthermore, anxiety and fear are deeply intertwined with the stuttering experience, often creating a self-perpetuating cycle. The anticipation of stuttering leads to anxiety, which in turn increases physical tension and the likelihood of a block, thus reinforcing the fear.

Treatment and the Path to Greater Fluency.

The pivotal question remains: Can stuttering be cured?

The most accurate answer is that there is no single, guaranteed cure that works for every individual, primarily because the underlying neurological mechanisms are still not fully understood.

However, highly effective treatments exist that can significantly reduce stuttering severity, improve fluency, and enhance overall quality of life.

For most children, the condition resolves naturally; for those who persist, early intervention is key to preventing the condition from embedding itself into the adult communication pattern.

The Mainstay.

Speech-Language Pathology.

Speech Therapy (or Speech-Language Pathology – SLP) is the cornerstone of treatment for all ages. Therapists employ various techniques tailored to the individual:

• Fluency Shaping: Focuses on how a person speaks, training them to use strategies to promote easy, continuous speech, such as a slower speaking rate, gentle voice onset, and controlled breathing.

• Stuttering Modification: Focuses on how a person stutters, teaching the individual to manage moments of disfluency with less tension and struggle, thereby reducing the associated physical effort and emotional distress.

• Lidcombe Program: A behavioral therapy specifically for young children, involving parents in praising and encouraging fluent speech and gently correcting disfluent speech.

Pharmacological and Neurological Avenues.

While speech therapy remains the primary approach, the neurological basis of stuttering has spurred research into medications.

Research has shown that some PWS have excessive dopamine activity in certain brain regions, which may suppress areas critical for fluent speech.

Medications that modulate the dopamine system have shown promise in some trials, particularly those that target the brain’s striatum (caudate nucleus and putamen), which is key for motor control.

However, these treatments are not widely adopted due to variable results and potential side effects, and they are generally not considered first-line treatment.

The Emotional and Psychological Component.

Given the significant psychosocial impact of stuttering, treatment must extend beyond speech mechanics:

• Psychotherapy and Counseling: Techniques like Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) are crucial for addressing the social anxiety, fear of speaking, and low self-esteem that often accompany persistent stuttering.

The goal is to reduce the negative impact of stuttering on a person’s life, regardless of the level of physical fluency achieved.

• Creating a Supportive Environment: For children, establishing a relaxed, pressure-free home environment where parents model a slow, unhurried speaking pace is a vital supportive strategy.

A Future of Clearer Voices.

Stammering is a complex, neurodevelopmental disorder rooted in differences in brain structure and function, exacerbated by genetic predisposition and environmental factors.

While the dream of a universal ‘cure’ where everyone speaks with maximum clarity is appealing, the reality is a spectrum of effective, individualized treatments.

By combining the latest findings on its neurological and genetic basis with time-tested speech and psychological therapies, researchers and clinicians are continuously improving the outlook for people who stutter.

The future of stuttering treatment lies in early, specialized intervention that empowers individuals to communicate effectively and confidently, proving that a disrupted flow of speech does not equate to a diminished voice.

Have a Great Day!